Our First Put Sell Pays Off Early With Kirkland Lake Gold

Less than a month ago, I introduced put selling to War Room members. In The War Room, we’re all about using every strategy in the book to make money.

After a survey, we found that many members love to sell puts…

However, some members don’t, and that’s okay too, as we have plays for every level of investor comfort.

Put selling is an advanced strategy used by investors like Warren Buffett. These investors use put selling to buy stocks they really want to own at discounts to the market price. Others use put selling to rack up income and trading profits.

The goal with put selling in The War Room is to trade for profits and generate quick income. But the cardinal rule for put sellers is to not sell a put on a stock they are not comfortable owning… at the right price.

Let me walk you through our Kirkland Lake Gold (NYSE: KL) play to show you what I mean.

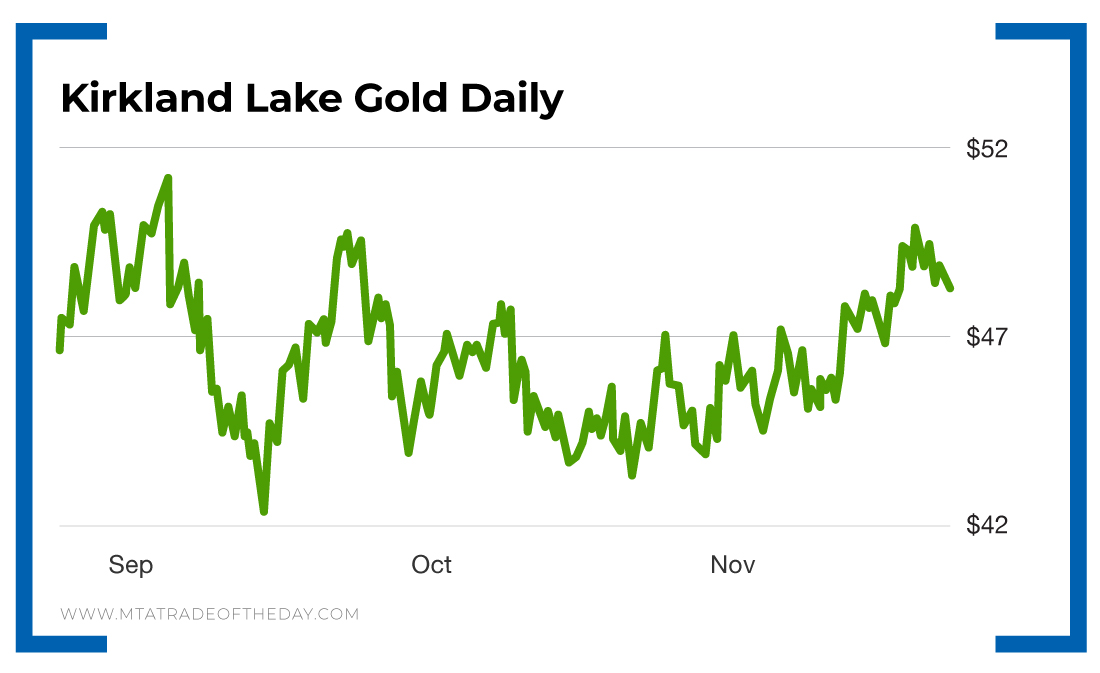

At the time of the recommendation, Kirkland Lake Gold was trading for around $45. This company is a top-tier gold producer with great profitability and cash flow. But gold is a finicky metal, and the price of gold stocks is directly correlated to gold prices.

So this play was for those who were interested in adding a great gold stock to their portfolio at the right price, or making a great return for trying to do so.

I chose the January 2021 $25 puts. Keep in mind that the strike was 44% below the stock price at the time of the recommendation. That’s a huge discount and a massive cushion in case of a drop. While the expiration date was more than year out, our expectation was to close well before the expiration.

Two weeks after the play, Kirkland Lake Gold reported stronger earnings and a dividend raise. While the price of gold stayed stable, the price of Kirkland Lake Gold began to rise.

I recommended members sell their puts for $1.05, and this week they bought those same puts back for $0.75.

Action Plan: We have two more put sells in the portfolio right now!

[adzerk-get-ad zone="245143" size="4"]About Karim Rahemtulla

Karim began his trading career early… very early. While attending boarding school in England, he recognized the value of the homemade snacks his mom sent him every semester and sold them for a profit to his fellow classmates, who were trying to avoid the horrendous British food they were served.

He then graduated to stocks and options, becoming one of the youngest chief financial officers of a brokerage and trading firm that cleared through Bear Stearns in the late 1980s. There, he learned trading skills from veterans of the business. They had already made their mistakes, and he recognized the value of the strategies they were using late in their careers.

As co-founder and chief options strategist for the groundbreaking publication Wall Street Daily, Karim turned to long-term equity anticipation securities (LEAPS) and put-selling strategies to help members capture gains. After that, he honed his strategies for readers of Automatic Trading Millionaire, where he didn’t record a single realized loss on 37 recommendations over an 18-month period.

While even he admits that record is not the norm, it showcases the effectiveness of a sound trading strategy.

His focus is on “smart” trading. Using volatility and proprietary probability modeling as his guideposts, he makes investments where risk and reward are defined ahead of time.

Today, Karim is all about lowering risk while enhancing returns using strategies such as LEAPS trading, spread trading, put selling and, of course, small cap investing. His background as the head of The Supper Club gives him unique insight into low-market-cap companies, and he brings that experience into the daily chats of The War Room.

Karim has more than 30 years of experience in options trading and international markets, and he is the author of the bestselling book Where in the World Should I Invest?