Economic Inequality: Loving the Poor… or Hating the Rich?

- Economic inequality is a hot-button issue, especially when so many highly educated people are living paycheck to paycheck.

- Today, Alexander Green begins to clear up some common misconceptions and set you on the path toward wealth creation.

In this series, I intend to show readers how to end economic inequality. Or, at least, the only kind they can do something about.

Not the gulf between the rich and the poor, but the one between your current net worth and the one you’d like to have.

Narrow that and you’ll be moving toward your most important financial goals – and lessening economic disparity in the process.

I promised to begin by dispelling a few common misconceptions about economic inequality.

In an earlier column, for example, I wrote:

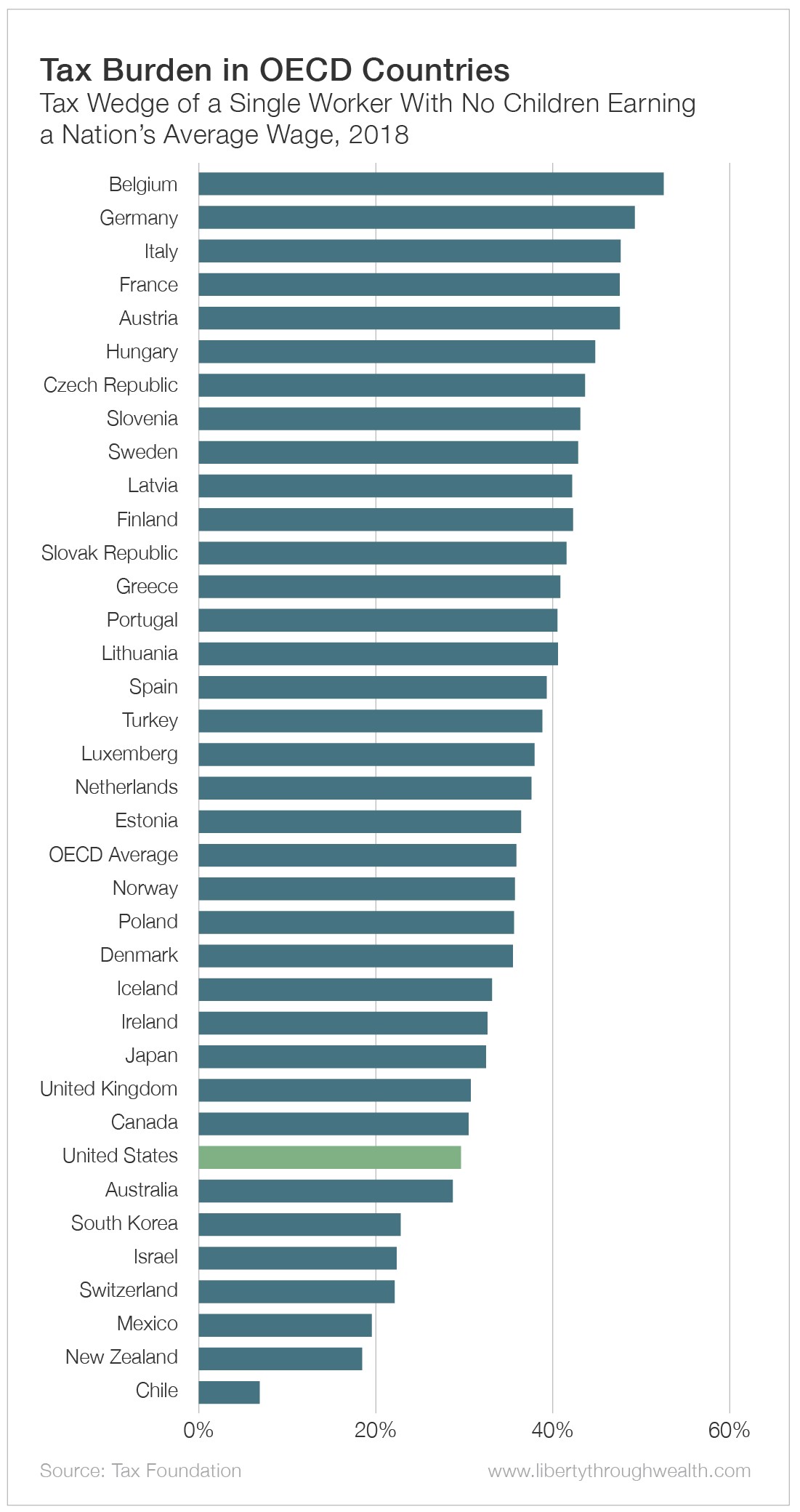

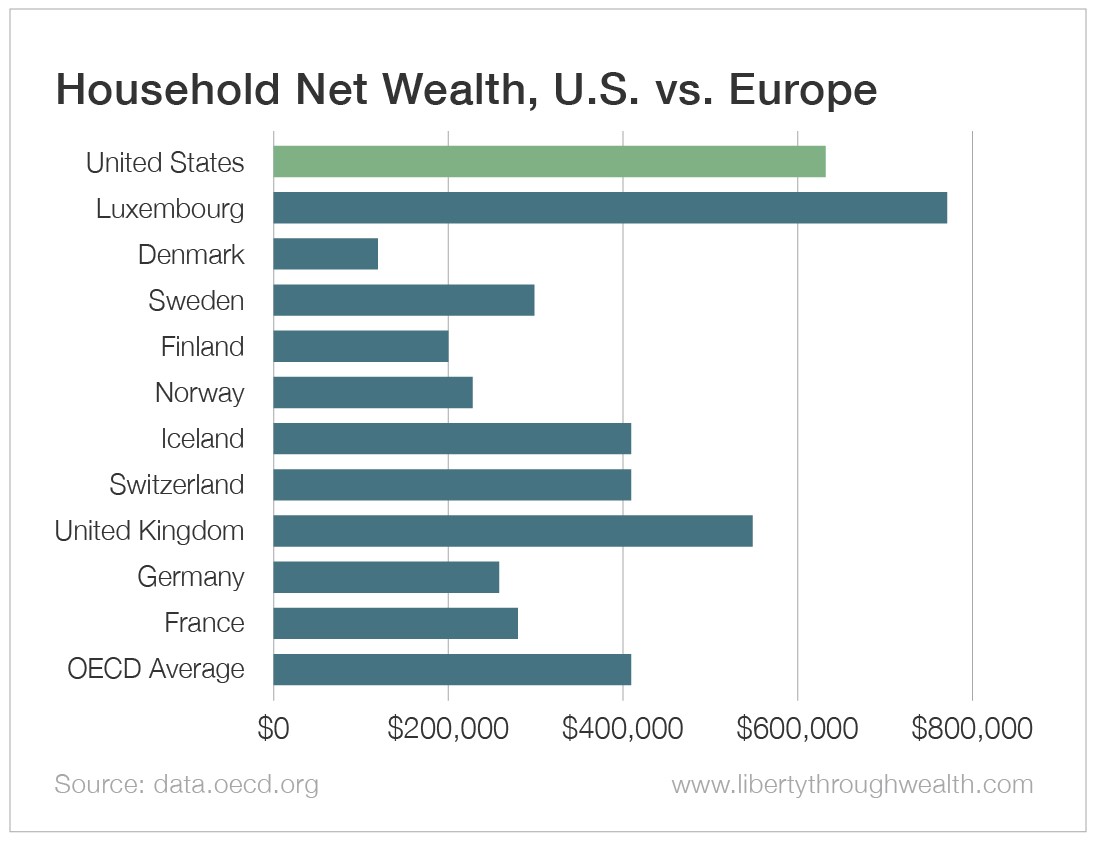

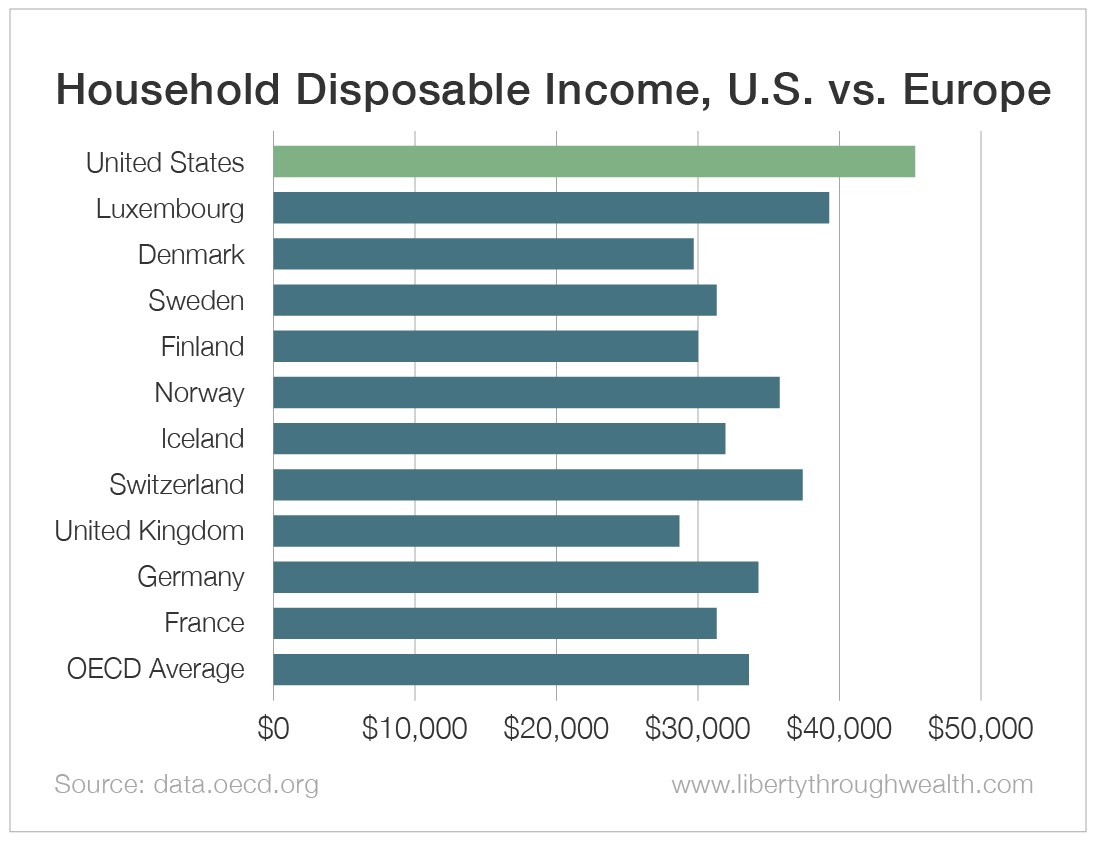

In a free country, there will always be economic inequality. The least free countries – North Korea, Cuba and Venezuela, for example – have the greatest economic equality. And those countries with the most generous income redistribution – as in most of Western Europe – have stagnant economies, high unemployment, lower annual income, less household net worth and much higher taxes.

Several readers wrote to dispute this last statement, insisting that Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren would not push us toward “the European model” if the people in those countries were economically worse off.

Unfortunately, some people don’t know the difference between a fact and an opinion – or, for that matter, the difference between making an argument and making an assertion.

Consider, for example, the claim that “the rich don’t pay their fair share of taxes.”

That opinion might be valid or invalid, depending on whom we define as “rich” and what we define as “fair.”

On the other hand, if someone claims that “the top 1% of income earners in the U.S. pay more in income taxes than the bottom 90%,” that is a fact, one from a reliable source, the Internal Revenue Service.

The assertion that folks in Europe don’t pay higher taxes and have smaller incomes and lower household net worth is easily refuted.

Here are just a few credible charts provided by Oxford Club Research Associate James Hires:

Why would some folks knowingly agitate for greater equality at the cost of less prosperity for everyone?

It’s a good question with several possible answers.

One is that they really don’t mind sacrificing some freedoms – even the most profound freedoms – if it results in more parity.

For instance, I have a younger brother who dropped out of The College of William & Mary during his sophomore year to join a commune.

This was not just a youthful infatuation. He still lives in one, although the proper name is “an intentional community.”

His son, raised in an environment of radical equality – no one living in a commune has much personal wealth or material possessions – returned from a trip to Cuba last year. And he was gushing.

“No one has more than they need,” he said. “No one has more than anyone else. It’s a beautiful thing.”

Cubans, of course, are the most politically repressed people in the Western Hemisphere.

I had returned from a trip to Havana myself, just a few months before my nephew.

The people – while bright, energetic and creative – are desperately poor, without freedom of speech, freedom to open a business or even freedom to leave the country.

The store shelves are mostly empty. One grocery store I entered had row after row of absolutely nothing.

Finally, I saw a counter with a large collection of bottles. On closer inspection, it was vinegar, dozens of bottles of vinegar.

Welcome to utopia in the eyes of radical egalitarians.

Another reason some people are worked up about economic inequality is not that they are terribly concerned about the poor. What really gets them exercised is rich people.

Europeans, in particular, have a long tradition of hostility toward “the wealthy.” And for good reason.

For centuries, most of the wealth on the continent was inherited or stolen (or both).

Virtually everyone worked for royals, aristocrats and other “nobles” who had done little or nothing to earn what they had.

Contrast that with today’s market-based economy, where all have an opportunity to rise, transactions are voluntary and for mutual benefit, and the wealthiest individuals – like Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates – have generally done the most to transform society for the better.

U2 singer Bono, originally from Ireland, commented on this phenomenon in a conversation with Oprah Winfrey:

In Ireland, people have an interesting attitude toward success. They look down on it… In America, you look up at the house on the hill, the mansion on the hill, and say, “One day… that could be me.” In Ireland, they look at the mansion hill and go, “One day I’m gonna get that bastard.”

In truth, much of the passionate rhetoric about economic inequality is driven not by a desire for social justice but by jealousy, envy and resentment.

It’s about taking the economically successful down a peg – or down altogether.

That attitude – not surprisingly – is not conducive to wealth building.

After all, who aspires to become what they despise?

In my next column, we’ll look at the fallacies behind the economic inequality movement – and discuss how you can use common misperceptions about it to make yourself and your family considerably richer.

[adzerk-get-ad zone="245143" size="4"]About Alexander Green

Alexander Green is the Chief Investment Strategist of The Oxford Club, the world’s largest financial fellowship. For 16 years, Alex worked as an investment advisor, research analyst and portfolio manager on Wall Street. After developing his extensive knowledge and achieving financial independence, he retired at the age of 43.

Since then, he has been living “the second half of his life.” He runs The Oxford Communiqué, one of the most highly regarded publications in the industry. He also operates three fast-paced trading services: The Momentum Alert, The Insider Alert and Oxford Microcap Trader. In addition, he writes for Liberty Through Wealth, a free daily e-letter focused on financial freedom.

Alex is also the author of four New York Times bestselling books: The Gone Fishin’ Portfolio: Get Wise, Get Wealthy… and Get On With Your Life; The Secret of Shelter Island: Money and What Matters; Beyond Wealth: The Road Map to a Rich Life; and An Embarrassment of Riches: Tapping Into the World’s Greatest Legacy of Wealth.