The Greatest Investor in History

- Who is the greatest investor in history? It’s not Warren Buffett or George Soros…

- Nicholas Vardy explains how this lesser-known investor ignored modern financial theory and created the best-performing quant fund ever.

So who is the greatest investor in history?

Most investors would say Warren Buffett.

Despite trailing the S&P 500 over the past 15 years, Buffett has a cult-like following across the globe. A search for Buffett’s name on Amazon reveals more than 4,000 results.

Those in the hedge fund world would point to George Soros. His high profile – and highly profitable currency bets – have certainly earned him a place on the Mount Rushmore of investors.

As it turns out, neither Buffett nor Soros stands at the top of the heap.

Instead, the crown belongs to a former mathematics professor named Jim Simons.

The Wall Street Journal‘s Gregory Zuckerman called Simon’s secretive hedge fund Renaissance Technologies “the greatest moneymaking machine in Wall Street history.”

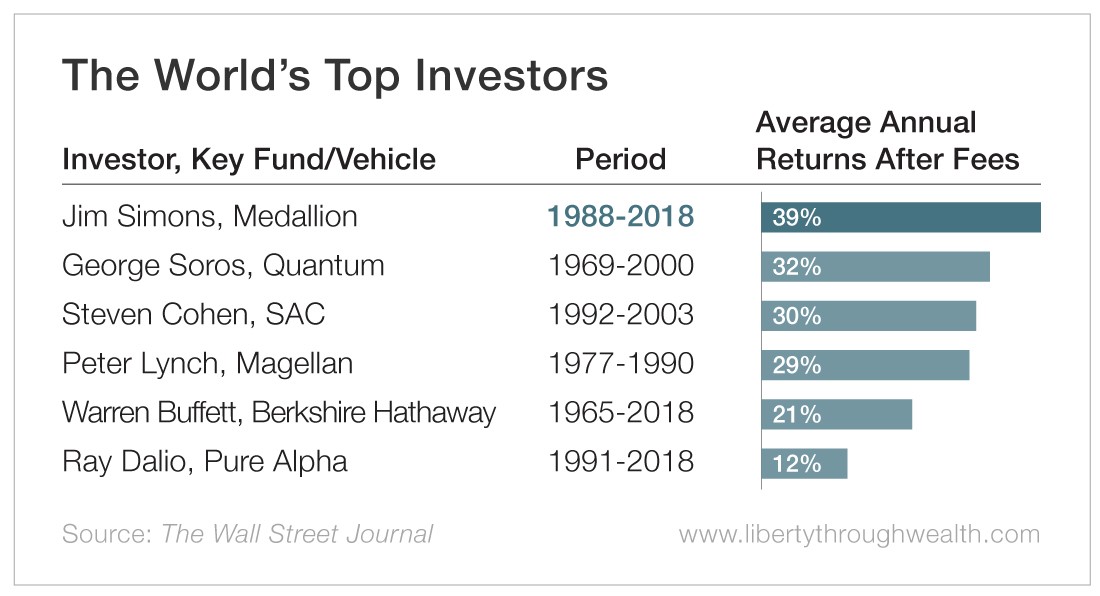

Since 1988, Renaissance’s flagship Medallion Fund has generated average annual returns of 66% before fees. That shrinks to 39% after hefty fees – 5% of all assets managed and 20% of all gains.

The Medallion Fund has generated more than $100 billion in trading profits since 1988.

No other investor comes close.

And that includes not only Buffett and Soros, but also other iconic names like Peter Lynch, Steve Cohen and Ray Dalio.

The top investors’ strategies often sound deceptively simple.

Buffett invests in high-quality companies. He then relies on the miracle of compound interest to work its magic.

Soros swings for the fences. He bets on the outcome of macroeconomic disruptions for outsized returns.

In contrast, Simons works with an army of rocket scientists to spot patterns others can’t see.

To put it in chess terms… Buffett is Bobby Fischer, Soros is Garry Kasparov and Simons is the head of the team running IBM’s Deep Blue – the computer that defeated Kasparov in 1997.

A Persistent Genius

There is little doubt Simons is smarter than your average bear.

Born in 1938 in Boston, Simons is the son of a shoe factory owner. After attending MIT, he earned his Ph.D. from Berkeley by the age of 23. Simons became the National Security Agency’s leading codebreaker by 26. He won geometry’s top academic prize at 36.

Eager for a new challenge, he abandoned academia by age 40. He had a singular objective: to get rich by trading the markets.

Simons opened up shop in 1978. He started by looking for patterns in currencies. He chalked up some early successes with simple technical strategies.

But it wasn’t all sweetness and light.

Unlike Buffett and Soros, Simons wasn’t a success from the get-go. Renaissance racked up significant losses. Returns were so bad that Simons had to stop trading. Employees feared the fund would close up shop.

Simons was distraught. He feared that he was “just some guy who doesn’t really know what he’s doing.”

But he persisted.

The Unique Renaissance Style

Fellow mathematician René Carmona convinced Simons to translate his investment decisions to algorithms. This approach applied machine learning to investing in the markets.

It was also a good fit for Simons. After all, mathematicians and scientists saw patterns where finance professors saw randomness. They could penetrate the chaotic world of the markets.

A team of computer scientists based in Berkeley, California, found reliable and repeatable short-term patterns in the market.

Renaissance changed its trading strategy. Holding positions for just a few days, it became the equivalent of a gambling casino. Medallion placed thousands of trades. And it only needed to profit from a bit more than half of its wagers.

The breakthrough year was 1990 when the Medallion Fund scored a gain of 55.9%. Renaissance was off to the races.

That said, its strategies suffer from certain limitations. Notably, Renaissance makes its money from short-term trades. The narrower the time frame, the larger the market inefficiencies. And the higher the chance that an algorithm will succeed.

It also means that the strategy has a limited ability to scale. Yes, Renaissance trades all patterns “to capacity.” And it keeps adapting its model to stay ahead of the competition. Nevertheless, the Medallion Fund has never traded more than $10 billion.

In contrast, Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway has $128 billion in cash on its balance sheet. Dalio’s Bridgewater has more than $150 billion under management.

Simons’ approach makes him an outlier in the world of investing. Most notably, Renaissance’s extraordinary results pose a direct challenge to modern financial theory.

Modern finance professors argue that the market is random. All information is already reflected in prices. And these economists have a fistful of Nobel Prizes in economics to prove it.

Legions of the world’s MBAs and CFAs are trained in this paradigm. Like Jesuits, they spread the gospel of modern financial theory all over the world.

In contrast, Simons avoids publicity. Unlike Soros or Dalio, you don’t see Simons opine on global markets in the media. Nor does he write books expounding his theories.

That secrecy has been a big part of Renaissance’s success.

After all, why would the market’s most successful casino ever reveal its edge?

[adzerk-get-ad zone="245143" size="4"]About Nicholas Vardy

An accomplished investment advisor and widely recognized expert on quantitative investing, global investing and exchange-traded funds, Nicholas has been a regular commentator on CNN International and Fox Business Network. He has also been cited in The Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, Newsweek, Fox Business News, CBS, MarketWatch, Yahoo Finance and MSN Money Central. Nicholas holds a bachelor’s and a master’s from Stanford University and a J.D. from Harvard Law School. It’s no wonder his groundbreaking content is published regularly in the free daily e-letter Liberty Through Wealth.