Warren Buffett’s Success Is Due to Skill, Talent and Experience

- In a recent article, Nicholas Vardy shared his view that Warren Buffett’s investing luck may finally be running out.

- Today, Mark Skousen shares a contrasting view – that Buffett’s skillful and knowledgeable investment strategies will stand the test of time.

“I also believe Buffett is right in attributing his world-beating success to luck.”

– Nicholas Vardy

In a recent article, my good friend Nicholas Vardy made the argument that Warren Buffett became the world’s most successful investor largely by luck, not skill.

Say again?

Could it be true that Buffett’s remarkable success as an investor is no better than someone who has a winning streak at blackjack or on the roulette wheel, or getting 10 heads in a row flipping a coin?

Having been a devoted student of Buffett’s investment techniques, a longtime shareholder of Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE: BRK-B), and someone who has personally interviewed the Oracle of Omaha and attended his annual shareholder meeting, I strongly disagree.

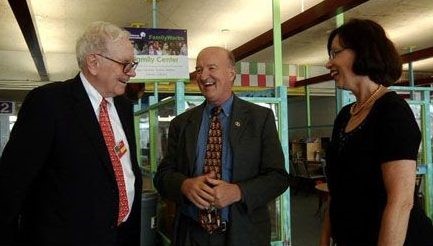

Buffett (left) shares a light moment with Mark and his wife in New York, 2010.

Buffett (left) shares a light moment with Mark and his wife in New York, 2010.

As Nicholas notes, Buffett has become the third-wealthiest person in the world as a result of the unbelievable success of his investment company since 1965. He has beaten the market the vast majority of the time.

Over the past 54 years, he has outperformed the S&P 500 (including dividends) 37 times, or 69% of the time. Berkshire’s total return through 2018 is 2,472,627% compared with the S&P 500’s 15,019%.

The compounded rate of return is more than double the stock index: 20.5% a year for Berkshire, 9.7% for the S&P 500.

Bear in mind that Buffett has accomplished this remarkable feat by investing in hundreds of public and private companies.

Has Buffett Lost His Magic Touch?

Nicholas claims that the stock market index has beaten Berkshire’s performance since 2004, but it depends on how you look at it. Over the past 15 years, Buffett’s investment company has beaten the S&P 500 10 times – a 67% win rate.

This year may well be an exception – the S&P 500 is ahead 18%. Meanwhile, Berkshire has zero return, thanks in part to a big loss in Kraft Heinz Company, a large position in bank stocks and the fact that it’s sitting on $122 billion in cash. Berkshire also took a hit a few months ago when a major institutional pension sold most of its position.

But this isn’t the first time Buffett has taken a hit while the market has fared significantly better. This kind of disparity has occurred a few times in the past, such as in 1975, 1984, 1999 and 2009.

Nicholas also noted that Buffett’s estate plan for his wife recommends a 90% investment in a stock index fund and 10% in government bonds – meaning she should not count on his investment company to outperform in the future. There’s no doubt that it is gradually becoming more difficult for him to beat the market.

Buffett blames the size of his investment company. In his 2014 annual letter to shareholders, he admitted that “Berkshire’s long-term gains… cannot be dramatic and will not come close to those of the past 50 years. It is harder to double the market value of a $100 billion company than a $1 billion company.”

However, that’s a far cry from saying that Buffett’s business-minded investment strategy is based on luck, like playing the slot machines in Vegas.

Is his systematic strategy really all for naught and simply based mostly on his good fortune?

Proving the Efficient Market Theory Wrong

In his younger years, Buffett was scornful of the efficient market theory (EMT) and index investing.

Back in 1988, he wrote a highly critical review of the EMT in his annual report to shareholders. Referring to the academics who defended it, he said, “Observing correctly that the market was frequently efficient, they went on to conclude incorrectly that it was always efficient. The difference between these propositions is night and day.”

As an example, he used the arbitrage methods of his mentor – the father of value investing – Benjamin Graham to prove his point:

The continuous 63-year arbitrage experience of Graham-Newman Corp., Buffett Partnership and Berkshire illustrates just how foolish EMT is… While at Graham-Newman, I made a study of its earnings from arbitrage during the entire 1926-1956 lifespan of the company. Unleveraged returns averaged 20% per year. Starting in 1956, I applied Ben Graham’s arbitrage principles, first at Buffett Partnership and then Berkshire. Though I have not made an exact calculation, I have done enough work to know that the 1956-1988 returns averaged well over 20%…

Over the 63 years, the general market delivered just under a 10% annual return, including dividends. That means $1,000 would have grown to $405,000 if all income had been reinvested. A 20% rate of return, however, would have produced $97 million. That strikes us as a statistically significant differential that might, conceivably, arouse one’s curiosity.

Buffett noted in his report that applying Graham’s arbitrage techniques involved hard work and very little luck.

Buffett’s Method of Buying Undervalued Companies

Over their 54 years running Berkshire, Buffett and his partner Charlie Munger have fine-tuned their competitive advantage. At an early stage, Buffett adopted Munger’s No. 1 lesson of investing: “A great business at a fair price is superior to a fair business at a great price.”

They are value investors who seek companies that will grow over time due to good management and long-term profitability. To find these companies takes a great deal of research and knowledge. Most of the time they are right.

Berkshire doesn’t buy turnarounds or try to replace managers. They have a hands-off management style. They don’t get involved in day-to-day operations like the Koch brothers. They try to buy companies that are already well-run at a reasonable price.

Buffett and Munger are also always in a good position to offer a cash deal and superior financial flexibility to private and public companies. As Buffett states, “We have some significant advantages in buying businesses over time. We would be the preferred purchaser, I think, for a reasonable number of private companies and public companies as well.”

In sum, I don’t plan to sell my Berkshire stock anytime soon.

If I were a betting man, I’d put some of my money on the symbol BRK-B.

I also have been recommending for years a financial income stock that has outperformed the market and Warren Buffett since going public in 2007. Click here for more information.

[adzerk-get-ad zone="245143" size="4"]